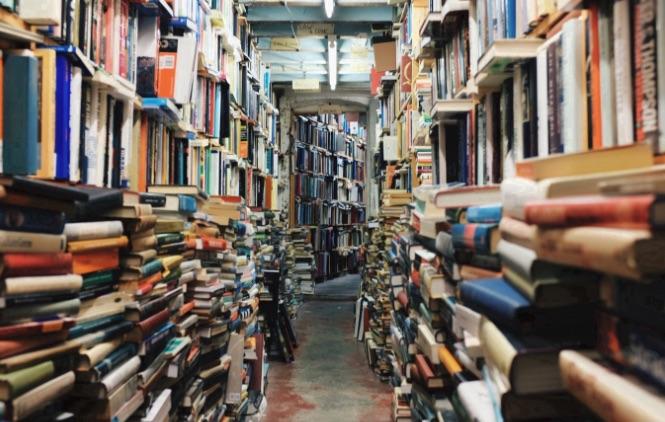

The atmosphere inside the Books & Books was quiet, but hospitable and soothing. A rainbow trove of books surrounded the patrons as they leafed through the shelves and conversed in hushed voices. Neutral Milk Hotel blared softly in the background.

We settled into the high top stools overlooking Main Highway. Thick condensation clouded the half-moon windows of the second floor, trickling down onto the terracotta brick sidewalk. In the city where she once saw no future as a writer, Mary Block now sits down with us to reflect on her successful career.

Block is a Miami-based poet and editor for nonprofit poetry journal SWWIM (Supporting Women Writers In Miami). She has been recognized as a Pushcart Prize nominee, a Ruth Lilly Poetry Fellowship finalist, and a Best of the Net 2018 finalist. Her work has been featured in numerous publications, and her first poetry anthology, “Love From the Outer Bands”, was recently published this past May. Her style is lyrical and raw, aiming to encapsulate the duality of living and loving in Florida.

The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What first brought you into writing?

I always loved writing. I was an English major as an undergrad, and then I was trying to find ways to make a living as a young writer in New York City. I did internships with several magazines, and I worked freelance for a while. But then, I just realized that I really wanted to be a poet. I thought, ‘I’m never going to make any money, but this is what I love and I’m going to go for it,’ so I applied to NYU and started pursuing a real literary life after that. Instead of trying to make myself kind of fit into a more “normal” career path, I just went for the oddball path. So far, it’s working out.

Writing is so diverse. What drew you to poetry in particular?

I often think poetry kind of chooses you. I was trying to get away from it. I was trying to do something more normal, more lucrative, with more of a clear career path. But I loved it. I love learning about where words come from, what they mean, what they say about people. I’ve just always been fascinated by language and words and the sounds of words. So for me, poetry is just the apex of that.

What was your mindset like when writing “Love from the Outer Bands”?

Some of the first poems were written when I was in grad school, 15 years ago. I moved, I had kids, I had different jobs, I was teaching. So it really took a while for any overarching theme to really come together within the book.

But when I think about it, it’s really about Miami and Florida as a mirror for the act of loving somebody. This is a fragile and dangerous place, but it’s also a really beautiful place that so many people love. That’s kind of what loving anybody is like: it’s fragile and dangerous but you can’t help going back to it.

How does Miami influence your writing and your identity as a writer?

When you live in a place like this, you have to love change. You have to love a place that very well might get destroyed by a huge storm in the next few weeks. A place that started as this tiny backwater and then grew through extraordinary circumstances and the influence of all different sorts of people into this incredible metropolis.

This is such an incredible place. It can’t help but influence who you are, wherever you go, whatever you do. It’s so, so deep within you. Living in such a gorgeous but terrifying place has kind of become the overarching metaphor of my life. Having a neat, orderly life is an illusion that is constantly being poked at. Nature is always sort of saying “Not so fast! Here’s a little lizard coming at you! Here’s a Palmetto bug coming out of your toilet!” It’s always there to remind you that you think you’ve got it all figured out, but you don’t.

Often, you write about both the anxieties and extreme joys of love and motherhood. How much of this is informed by your personal life?

It’s the jumping off point for everybody, right? We’re all working out of and from our own experiences.

My father died when I was very young, so my experience being a parent is for sure colored by that experience. That experience happening to me when it did had all these echoing effects. I’m constantly in my own head thinking about allowing my children to have rich, full lives without projecting my own anxiety onto them.

I try to be a faithful person. We believe in a God that accompanies us through bad things, that helps us to have hope that this horrible thing that has happened is not the final reality. So, that’s the way I think about experiencing loss and how it affects the way that I think and write.

Did you have a set destination in mind as you were putting this book together?

No, I did not have a set destination in mind. What I have is obsessions. What are my obsessions? Being a parent, living in South Florida, having placed my family in the path of these terrifying storms because this is a place that I love. Climate change, what it means to have even considered having children at the time that I did. So no, I did not have a project. The way the individual poems come about, you just have to be attuned to your own obsessions. It’s totally different from writing fiction.

What was your biggest challenge throughout the publishing process?

Just getting somebody to take the book. I submitted it 87 times, so I got rejected 86 times. It’s not like other career trajectories where you graduate from college and you do an internship here and then you get an entry level job there and you work your way up. You have to forge your own path, and it really is dependent on the community that you build around yourself and your work.

It’s been an extraordinary blessing to be a part of SWWIM. Being an editor definitely gives you insight into the publication process. It’s so subjective. There are oftentimes a lot of disagreements between me and my colleagues about what a “SWWIM poem” is, what fits within our aesthetic. Your work is just not going to be for everybody. It has to land in the right hands at the right time.

What kept you going through the rejections?

Well, I knew the work was good, and that it was important. The process is just so subjective and often influenced by factors completely out of your control. Knowing that kept me going. And that this is the life that I wanted. I wanted to be a writer. And I wanted to have a book in the world.

As far as being on the other side of having published a book, it’s not like all of a sudden everything is easy. But it’s definitely very legitimizing. Being able to talk and say, “Oh, my book,” gives me a feeling of having landed somewhere. It’s not the final landing, but it’s definitely a wonderful, wonderful stepping stone within my career.

What do you think the future of writing will be like, especially now with AI?

What’s the point of ripping off a poem? AI doesn’t need the prestige of having published. I think people will always want genuine stories and genuine connection. People will always want the inside of somebody else’s heart and mind.

The future of writing, I think, is very exciting. There’s so much more opportunity and community now, especially here, around writing. If you want to build a writing life, having third spaces like Books and Books, organizations like SWWIM that want to champion your writing, and people who care about literature and about creating opportunities for young writers is so critical. And it’s here in a way that it never was when I was your age.

Do you have any advice or tips for young writers?

Find your group. Find people who love what you do and want to help you create a life in writing, and don’t let them go. It truly is about community building in the writing life. It’s a very, very solitary act, but publishing is a group project. If you want a life in writing, find other people who also want a life in writing and keep them close to you.

To learn more about Mary Block and her work, consider checking out her personal site.

Bella Guitian • Oct 23, 2025 at 5:59 pm

so cool!