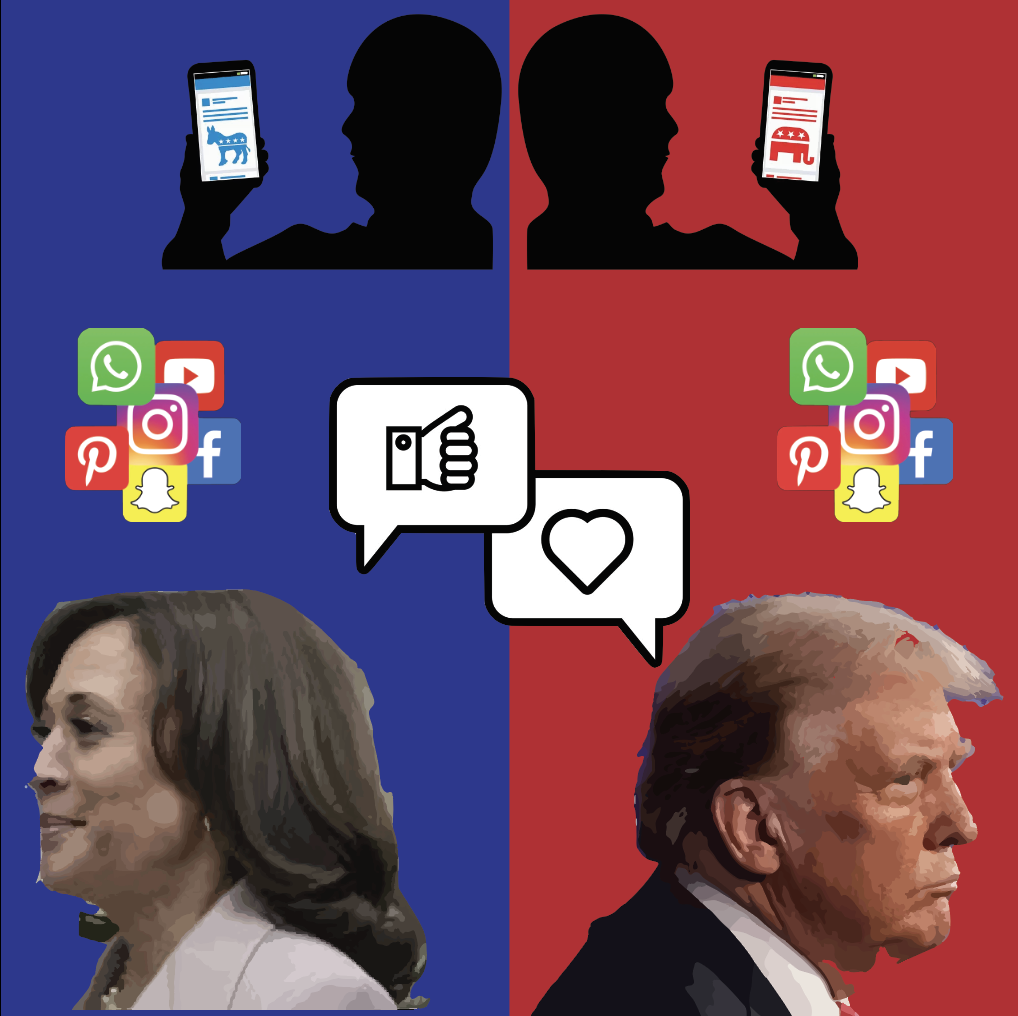

Our country has never been so polarized.

I’ve heard this for as long as I can remember. As an 18-year-old, I wasn’t exactly present in the political sphere before 2016, so my only experience with politics has been this increasingly heated and tumultuous scene.

If you’d asked me a couple of weeks ago, I would have told you that America is exceptionally polarized, both in policy stances and in how we view the opposing political party.

Even though I only use social media occasionally, I am very used to seeing comment sections on TikTok, Instagram, Youtube, etc., as political war grounds, where paragraphs of insults are volleyed back and forth. When I look at social media, any agreement between today’s Democrats and Republicans seems unfathomable to me.

However, according to research by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, American voters are actually less “ideologically polarized” than we think. In fact, research has shown that there is some overlap in policy preferences even on the most controversial issues. For example, polls have shown that a majority of Democrats and 4-in-10 Republicans support banning high-capacity ammunition magazines and creating a national database for gun sales.

So, if our actual policy stances don’t seem as crazy and immoral to the other side as we think, why do we feel more divided than we actually are?

This feeling can be attributed less to true ideological polarization, which can actually be good for democracy (in 1950, experts found that the U.S. needed more political polarization), than to something called “affective polarization,” which concerns the degree to which people see opponents as “abhorrent” and “unredeemable.”

Affective polarization is what makes it difficult to talk about politics in classrooms and with family; it is what threatens the foundations of our democracy by making compromise nearly impossible; and it is because of this that even if we agree on the same political principles, we cannot engage in dialogue enough to see it. It is not surprising that in 2021, researchers found that nearly six in ten American adults said they found it stressful to discuss politics with people who disagree, thus discouraging healthy, open dialogue.

But what has caused the growth of this polarization?

While political antipathy has been growing for two decades, the introduction of social media has fueled rage and distrust, making us feel attacked by opposing opinions. Jonathan Haidt, a social psychologist at NYU’s Stern School of Business, is careful to note that there are multiple causes for affective polarization–from election policies to in-group bias, but asserts that social media “has become a powerful accelerant for anyone who wants to start a fire.”

So how does affective polarization on social media work?

Haidt explains that the algorithms used by platforms such as Facebook and YouTube create echo chambers, media bubbles, and rabbit holes that limit information people consume and further entrench already deeply-held beliefs.

These echo chambers on social media reflect what users engage in most. So if someone were to “like” a post praising Marjorie Taylor Greene, his or her feed would show more content praising Taylor Greene. It makes it harder to find any voice that dissents from that idea.

What’s probably most harmful, however, is that when the algorithm does show users differing opinions, they are usually in an antagonizing light with a comment section filled with insults, mockery, or reasons to invalidate that opinion.

Research shows that social media warps our perceptions of the “other side,” deepening an already-present division into an insurmountable rift. According to The Conversation, social media operates “less as a mirror than as a distorting prism for the diversity of opinions in society,” meaning that the inflammatory comments and degrading debates we see online are not necessarily what most people on “the other side” would say or believe. Instead, the algorithms display the most hostile voices that vie for attention.

It’s important to note that when people post inflammatory or extreme content, many times they are more interested in declaring devotion to “their side” as an identity statement rather than attempting to persuade or engage in healthy debate.

And one of the main problems with social media is that it actually incentivizes people to do this.

According to Tristan Harris, co-founder of the Center for Humane Technology, “We are being rewarded for being division entrepreneurs.” Harris told 60 Minutes, “The better you are at innovating a new way to be divisive, we will pay you more likes, followers, and retweets.”

But as appealing as going viral may be, there is great danger in this, and even social media companies have recognized that some regulation is needed.

According to NYU academics, sites like YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram have adjusted their algorithms after heated, controversial political events including the spread of election misinformation in 2020 and the Capitol Insurrection on January 6th, suggesting that social media companies recognize that there is some correlation between the use of their platforms and these alarming events.

But since social media networks are designed around an engagement-for-profit business model, after a perceived crisis, the algorithm is dialed back up so as not to threaten user engagement.

So what can we do?

As a society, we need to recognize the threat these algorithms pose, and social media companies must make these “dialed down” algorithms permanent to stop fueling political antipathy and hatred. The corroding effects of social media should not be a question, but rather acknowledged as a reality we have to fight against.

We also need to take accountability for our own actions by paying attention to the information we receive on our feeds and the headlines we regurgitate. Before we repost or press “like,” we need to ask ourselves where these tweets, comments, and headlines are coming from, examining not only the sources, but the emotions and incentives behind them.

Before getting online, we should also challenge ourselves to find spaces outside of social media to engage in real-life political conversations with friends, family, and colleagues. That way, we can practice engaging in discussions with respect and compassion and resist falling into the temptation to make assumptions about the morality or integrity of other people.

And, most importantly, we need to take a look inside and think about our own voices. Are we the inflammatory ones seeking attention and inciting drama? And if so, how can we do better?

Whatever we do, we need to curb the extreme polarization we see online today. It has contributed to an intense erosion of trust in our democratic systems, elections, judicial processes, and even in scientific facts.

But if we remind ourselves we are not as divided as we think, maybe we can actually begin to appreciate diversity, learn to listen, and remember what, in the end, makes this country truly great.

Gabriel Alkon • Feb 14, 2025 at 5:33 pm

I entirely agree with the ideas expressed so effectively in this article. I hope that readers at Carrollton and beyond take your points to heart. Thank you, Ana!

Lyana Azan • Feb 14, 2025 at 12:43 pm

What a well-researched article! Thank you for this.

Sofia Barrera • Feb 13, 2025 at 11:34 am

This is such an important read. Amazing work Ana!