The origins of Halloween can be traced back over 2,000 years to the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain. Celebrated around the end of October and the beginning of November, Samhain marked the conclusion of the harvest season and the coming of winter. The Celts believed that during this time, the boundary between the worlds of the living and the dead thinned, allowing spirits to roam the Earth. To protect themselves from these wandering spirits, people lit bonfires and wore costumes to disguise themselves from harmful entities. This practice of dressing up has survived through the ages, manifesting today in Halloween costumes.

As Christianity spread through Europe, the Church often sought to replace or integrate local pagan festivals with Christianity. In the early 7th century, Pope Boniface IV introduced All Saints’ Day as a day to honor all Christian saints, especially those who didn’t have their own dedicated feast day. Originally celebrated on May 13th, the day coincided with the Roman festival of Lemuria, which honored restless spirits. However, in the early 8th century, Pope Gregory III shifted All Saints’ Day to November 1st. The night before All Saints’ Day, October 31st, became known as All Hallows’ Eve, later shortened to “Halloween.”

In America, Halloween’s transition into culture was slow and uneven due to the religious nature of early colonial settlements. In the 17th and 18th centuries, many colonists, particularly in New England, were Puritans who adhered to strict Protestant beliefs. These settlers viewed celebrations associated with witchcraft, paganism, or superstition as sinful, so Halloween was not widely practiced in these areas.

The massive influx of Irish immigrants fleeing the Great Famine brought their customs, including the practice of carving turnips and “guising” (costume-wearing), across the Atlantic, and in the southern colonies, such as Virginia and Maryland, there was more religious diversity and openness to festive customs. Early versions of Halloween-like gatherings in these regions may have involved harvest festivals, where communities came together to celebrate the autumn season, share stories of the dead, and engage in games like bobbing for apples. The Irish tradition of turnip carving was replaced with pumpkins, leading to the iconic jack-o-lantern. The association with the supernatural, though faint, started to take root in the South through ghost stories and folktales told around these communal gatherings.

After World War II, Halloween transformed into the family-friendly holiday we recognize today, largely due to the baby boom and the rise of suburban neighborhoods.

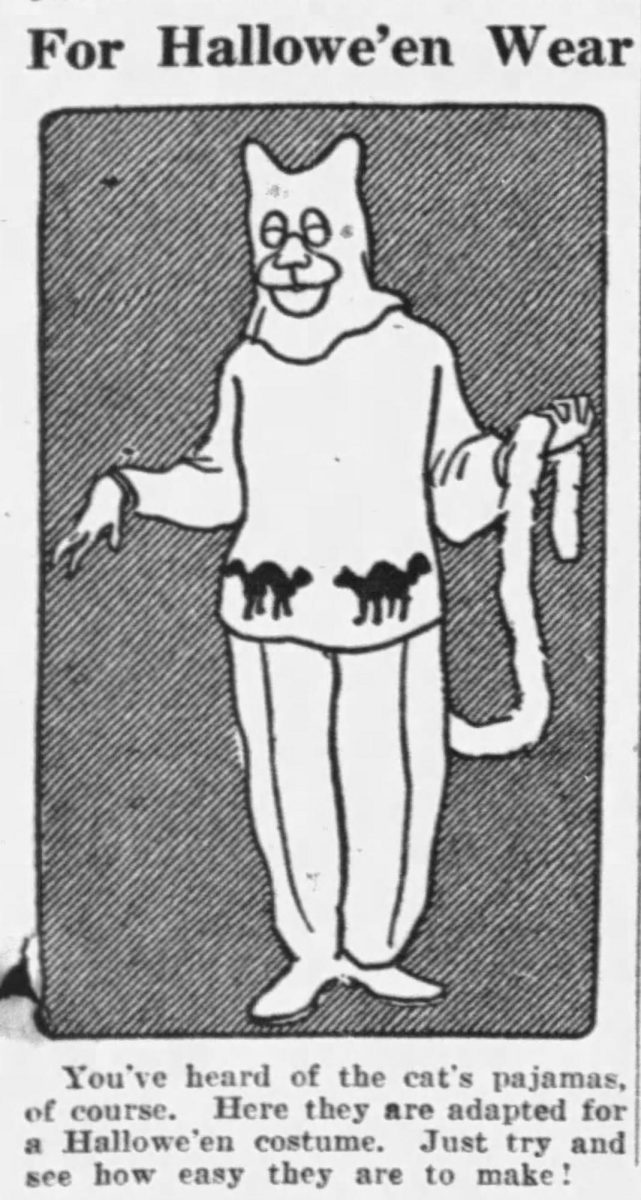

The post-war economy allowed for more disposable income, and American culture became increasingly consumer-driven. Candy companies and retailers saw Halloween as a perfect opportunity to market products, leading to the mass production of Halloween costumes, decorations, and candy. The first mass-produced costumes appeared in the 1930s, but by the 1950s, this became a booming industry.

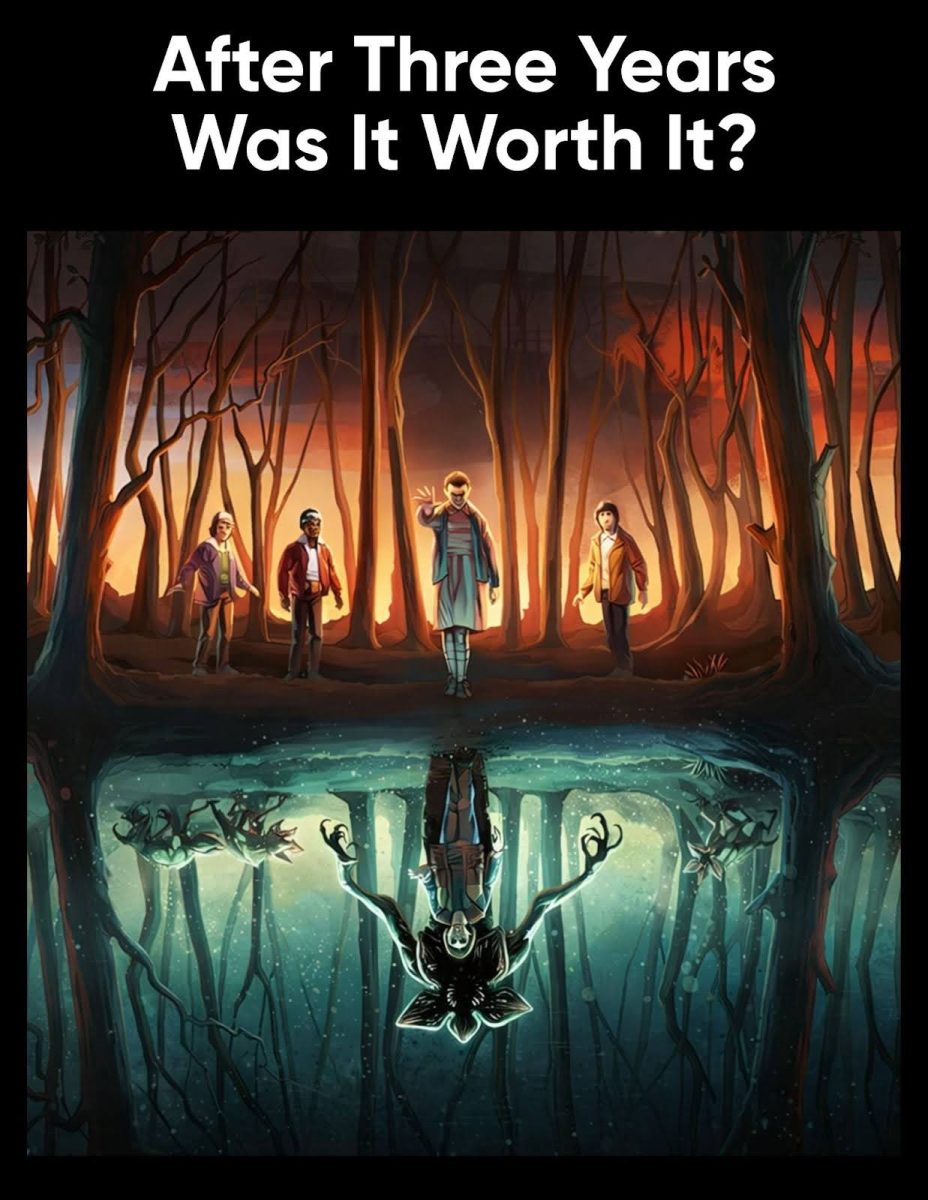

Television and movies also began to influence Halloween, with horror films and monster movies like Dracula and Frankenstein helping to cement the association of Halloween with scary creatures. Haunted houses became a popular form of entertainment, and Halloween-themed television specials like It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown helped solidify the holiday’s cultural significance. By the 1970s, horror films such as Halloween (1978) and Friday the 13th (1980) further embedded Halloween’s connection with the supernatural and the terrifying.

Today, Halloween continues to evolve, heavily influenced by pop culture. Costumes are now as likely to be inspired by the latest movie or TV show as by traditional ghosts and witches.